On the bus to Bayonne, 7:30a.m.

The rain continues, but the fog and mist add a cozy spice to the mountainous terrain and lush forest of the Pyrenees. Julio took us to a wok restaurant last night, in a largely successful attempt to get Mom her first cancer-smart meal. Thus far it has not been easy. It’s not possible to find a restaurant in Bilbao that will cook a meal before 8:30p.m., so if you want to eat before then, you must choose from among various bread-heavy pintxos (peenchos), known everywhere else as tapas, which, whether containing brie or salmon or crab, sport large dollops of what appears to be the regional spice of choice, mayonnaise.

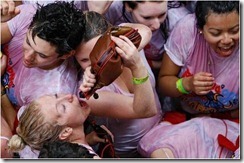

At the wok restaurant, I wanted a glass of red wine. Julio ordered a bottle, saying Spanish wine was predictably good if it cost more than 5 euros, but that if it cost less than that, your head would let you know. (“I woke up with a headache,” I would tell him the next morning. “At 3, 4, and 6 a.m.”) Julio drinks his wine like I drink water. When I returned from supervising the cooking of my food in the wok area the bottle was nearly empty. “Did you spill the wine?” I asked, looking under the table.

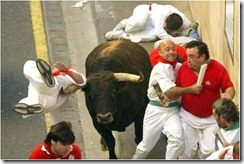

Bilbao is a lovely city, and one of the main cities of the Basque Country, a relatively autonomous region of Spain with a strong independent streak.

“Last night Real Madrid was beaten by a football club of beginners,” Julio announced when we met him this morning. “There will be suicides before it is light. But the rest of the country could not be more happy.” Madrid is the locus of the Spanish central government, and the people of both the Basque Country and the equally fiercely independent Catalonia love to see it fail.

While in Bilbao we visited the truly astonishing Guggenheim Museum, a sculpture far

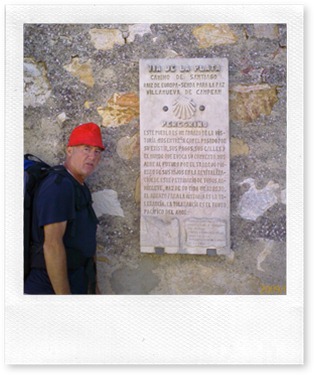

more impressive than the rather precious concept art we saw inside it. We walked along the Gran Via, Bilbao’s equivalent of Fifth Avenue, enjoyed the transparent, Art Nouveau shell-like entrances to the subways (called Fosteritos by the locals) that had been designed by English architect Sir Norman Foster, took in cityscapes enhanced by the Rio Nervion, ducked into our first Santiago Cathedral, complete with the trademark scallop shells on the exterior, toured the extraordinary multi-use Alhóndiga, each of whose dozens of giant inner columns were unique, and walked the pedestrian streets of Casco Viejo, the charming older part of town in which our hotel was located. We’d have to carry for hundreds of miles anything we bought, so, in spite of all the great shopping to be had, we bought nothing.

Julio says that the city was transformed almost overnight by the Guggenheim. Initially, he said (and I recall reading this in news reports), many people did not understand the strange new structure, and they did not like it. The estimate of 200,000 visitors in the first year was exceeded by 2.2 million, though, and Bilbaoans soon went from seeing themselves as a city of industry to a city of aesthetics, tourism, and cutting-edge design. Now there are many fine examples of modern architecture, a nice complement to the many beautiful older buildings, from the Gothic cathedrals to the Beaux Arts municipal building and Teatro Arragio.

We were up at 6a.m., never an easy task on one’s second morning of jet-lag, and at the bus station by 7. A young man with a backpack approached Mom, Carrie, and me while Julio was away.

“Excuse me,” he said. “Do you have a map of Spain?”

“No,” Mom said. “But our friend will be back in a minute.”

The man looked confused. I explained. “We decided to bring along a Spaniard instead.”

Now we wend our way through the forested hills, lulled by the hum of the bus and the sound of water against the tires. In the forested cleft of a misty mountain to my left I notice a sinuous thread of fog in the shape of a question mark.

I am writing this post largely in order to take my mind off my body, which is contorted fiendishly in seats that appear to have been designed and manufactured for, and perhaps by, small children. They’re so narrow that Julio and I are forced to cross our arms just to co-exist. The seats also come equipped with an anti-lumbar feature, surely patented, that sends the lumbar spine backward in space. Higher up, my middle and upper back are forced forward, after which the seat, also too short, again curves away, so that in order to rest my head it is necessary to throw it back and look up to the ceiling.

My knees are jammed tightly into the seat in front of me, kneecaps crushed against the grey plastic. Even to type these words, my hands must dangle from my chest like the useless appendages of a T. Rex. When the three-hour ride is over, I will require work by both a chiropractor and a shrink.

St. Jean Pied de Port is an hour away by train.