I was married, briefly. The nature channels tell me there are penguins with longer relationships.

I was married, briefly. The nature channels tell me there are penguins with longer relationships.

By the time a judge brought down the curtain, my mother and I were six thousand miles away, standing at a waystation on a yellow-arrowed path, like characters in some 21st century update to the Wizard of Oz. My mother wanted a cure for her cancer, or at least a break from “all the cutting and poison”, as she put it. I hadn’t believed there were any answers for my uncertainties high on the wild-dog-infested and wind-swept spine of a mountain range in northern Spain, so I had sort of convinced myself I wanted nothing.

I stood at the foot of a high rubbled mound. I was holding my new

I stood at the foot of a high rubbled mound. I was holding my new

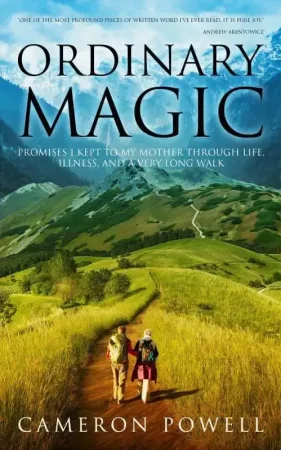

Camino de Santiago start

Inge in Bilbao, Spain, days before starting the Camino de Santiago

Nikon SLR, which I’d just bought from Costco via the rationale of this very trip. The video was on: Mom had talked about this moment for months, and I am nothing if not a catcher, or perhaps I mean a chaser, of moments. She was picking her way up the mound, through the powdery gray and white rocks. My fifteen-year-old second-cousin, Carrie, had abandoned her massive backpack and was watching the scene from my left. In a field to my right an older man, very tall, sturdy boots, backpack, was weeping.

Camino de Santiago Cruz de Ferro

Offerings left behind at the Camino de Santiago’s Cruz de Ferro

The mound was pierced at its summit by a thirty-foot-tall oak post, about as big around as a telephone pole. The very top of the post was fitted with an iron cap, like the sort of hat an English bulldog might wear, if an English bulldog had scored an audience with the Queen. For a structure with the grand appellation of El Cruz de Ferro, an old Spanish-Latin term that means Cross of Iron, the cap supported an almost comically tiny iron cross whose three free arms ended in fleurs-de-lis. For thousands of years, some version of the Cruz de Ferro had spied on countless pilgrims – first Pagan, later Catholic, now mostly Pagan again – as they formed meaning out of this very waystation.

For thousands of years a mound of rocks marked the summit of this mountain range. A million pilgrims before us had built up the mound with hand-placed relics from their own private rituals of letting go: of anger, of grief, of resentment, of illness – letting go even of the fear of death. Because that is what people do on pilgrimages, of any kind, whether they mean to or not. They let go. That’s what the verb to forgive means. To forgive others, and, harder yet, to forgive oneself. Jesus was telling us what he knew about forgiveness, but the bastards killed him before he could show us how to forgive ourselves.

An ancient tradition held that pilgrims should bring to the Cruz, from their own homes, a small stone and a more personal item, and to leave them behind at the Cross. My mother was now placing, among the rocks, a small stone she’d carried from an ancient canyon near her house in Colorado. Previous pilgrims had also brought and left behind other, more telling things. A tube of lipstick. A postcard of Bruges, scrawled in a woman’s hand. Folded pieces of paper and fragments of words in Spanish and English, German and Dutch, Korean and Basque. Underwear that raised certain questions. A Matchbox car that looked to my inner-nine-year-old’s eye like a ’68 Corvette, give or take two years. A toy soldier – missing a leg, poor bastard – and the half-eaten cookie on which he’d been subsisting among the pebbles.

On the wooden pole itself I could make out a tacked-up orange baseball cap and a clip-less biking pedal, a gourd on a string, a black-and-white photo of a European peasant family, circa 1930s, a 1970s photo of a boy, in a shirt with blue stripes, holding a Bible, a pre-printed fortune cookie’s fortune: Do not throw the butts into the urinal, for they are subtle, and quick to anger. I saw a Prada label, an AC Milan futbol jersey, and a broken pair of cheap sunglasses. A German pilgrim had erected a small German flag among the rocks. Not to be outdone, so had a Belgian. Or vice versa, let’s not start another war.

My mother, still with her back to my cousin and me, had reached the top of the mound. The Iron Cross now loomed over her, standing stoutly in the wind. She bowed her head and pulled her second, more personal offering from a pocket in her field jacket. She cupped it with both hands and held it over her head, a modest proposal to the cosmos about what she should be allowed to let go of. When I saw her shoulders start to shake I began to cry, too, but quietly, because I was the expedition videographer, not to mention its chief biographer, photographer, legal counsel, and practicing podiatrist.

I handed the camera to Carrie and went to join my mother.